In This Story

March 1 end of program will impact millions of Americans–predominantly families and people of color

On the same day National Nutrition Month kicks off, millions of individuals and families in the U.S. who currently receive benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assessment Program (SNAP) will see a decrease in their federal food benefits. On March 1, pandemic emergency allotments to SNAP are set to end–cutting benefits by $90 per month per person (on average).

Despite SNAP emergency allotments, many Americans still face food insecurity

During the COVID-19 public health emergency, food insecurity rates doubled overall throughout the nation and tripled in households with children. Congress originally enacted emergency allotments (EAs) during the pandemic to provide economic stimulus and address food insecurity. However, data shows that even though EAs kept more than 4 million people “above the poverty line,” according to a study from the Urban Institute, millions of Americans still experienced food insecurity and lived below the poverty line.

Evelyn Tomaszewski, MSW, assistant professor of social work in the College of Public Health at George Mason University, underscores the severity of the issue, saying: “Food insecurity was prevalent during the pandemic and will remain a serious concern in a ’post-pandemic’ world, particularly among households with children–who were most likely to face food insecurity during the pandemic–as well as communities of color (per USDA data).”

“When you are struggling to balance rent and daily living expenses, a loss of $168 or $190 can translate to hardship and extreme food insecurity,” said Tomaszewski. “In 2022, 9% of the population of Virginia, or 1 in 11 persons, accessed SNAP benefits. We are talking about our neighbors, our students, and our colleagues.”

A study by American University found that by the end of 2021, Americans were paying an average of 12 percent of their income on food; for lower-income wage earners, it was closer to 36 percent.

In 2023, an estimated 34 million people (including 9 million children) still remain food insecure, and the cost of food is expected to rise by 3.5 percent - 4.5 percent, according to the USDA.

Vulnerable populations already adversely affected by COVID will see the biggest impact

“Our country’s vulnerable populations have been the most affected by COVID and inflation. Those who live significantly below the poverty threshold, including households with children headed by single women and Black and Hispanic households, rely on SNAP benefits to make sure there is food on the table,” said Kerri LaCharite, PhD, associate professor of Nutrition and Food Studies in the College of Public Health.

LaCharite and Tomaszewski are also concerned for populations that will likely dip below the poverty line when EAs end, including college students, seniors living on a fixed income, and individuals with disabilities.

College students who qualified for the emergency allocation will also lose their benefits on March 1, when those defined as “able-bodied adults without dependents” will again be limited to a three-month limit of benefits. According to the College and University Food Bank Alliance, more than 30% of college students were food insecure in 2019, even before the pandemic.

Older adults and persons with disabilities saw a decrease in SNAP benefits when they received “long overdue (and still minimal) increase to social security benefits.” With the end of EAs, benefits will be cut (on average) by $168.00 per month for households with adults aged 60 and older and (on average) $190 per month for persons with disabilities.

The impact of food insecurity is long-lasting for children and adults. “The long-term effects of food insecurity will affect health outcomes. In children, food insecurity is associated with cognitive problems, higher risks of being hospitalized, asthma, behavioral problems, depression, poorer general health, among a longer list. In non-senior adults, food insecurity is associated with diabetes, hypertension, mental health issues, high blood cholesterol levels, and poor sleep,” said LaCharite.

Food banks, schools, and community support - How will individuals, families, and communities meet the need?

Erin Maughan, PhD, associate professor of nursing in the College of Public Health, works with K-12 school districts and school nurses and is particularly concerned about the impact on school-aged children, school systems, and the employees who may already be stretched thin.

“With SNAP emergency funds decreasing, it could increase the number of students or amount of food schools will provide students. Schools already are a safety net for food (breakfast and lunch), and some provide food backpacks for the weekend. Of greater concern is how it will impact mental health and learning. When children are hungry, they can't concentrate; down the road, it could also be an issue of malnutrition,” said Maughan

“Families are going to need to fill the gap somehow,” says LaCharite. “We have seen this in the past. It will likely mean increased reliance on food banks and pantries, skipping meals, and a significant decrease in the consumption of fruits and vegetables. Food insecure families buy less fruits and vegetables and buy more nonperishable staples as their budget for food shrinks.”

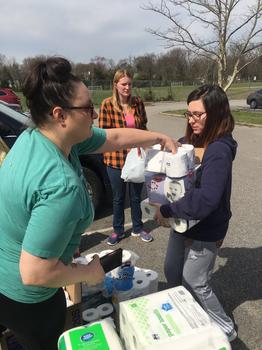

People are losing a significant amount of support money available via the SNAP EA, resulting in increased reliance on food banks (which are also consistently reporting both increased need and decreased donations.) While many of our area emergency food providers saw a temporary dip in need in fall 2021, they also experienced a large increase in patrons seeking food in the spring of 2022 as inflation rates started to rise.

What can be done to help?

March 1 is also the start of National Social Work Month, and Tomaszewski sees an important role for social work students and faculty–and beyond. In addition to donating to area food banks, there are ways that members of the community can help those experiencing food insecurity.

“At the macro or systems level, everyone can advocate for the Commonwealth of Virginia to add funds to the program that not only ensures SNAP benefits (at least) similar to the SNAP EA levels but also expands coverage to those that will be losing benefits, such as ‘able-bodied persons’ and college students,” says Tomaszewski.

She also sees an important role for those in the College of Public Health and beyond. “Social work students, and students throughout the College, directly work with those who will be affected by this policy change and/or who are at risk for food insecurity. At the individual level, social work students and allied professionals across the College can learn about food insecurity and available benefits, and ensure that clients know what is available, such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and SNAP.”

As the country recognizes National Social Work Month and National Nutrition Month, it is also an opportunity to recognize, support, and advocate for our neighbors, our students, and our colleagues who continue to experience food insecurity across the United States.