“Peace is a process, not a goal. And we’ve got to stay with it.”

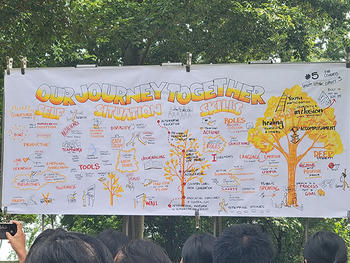

It was a sunny afternoon in mid-June. Graduate students in the 2022 cohort of the Lincoln Scholarship Program sat in the grass outside George Mason University’s Point of View International Retreat and Research Center in Lorton, Virginia, and watched as a graphic recorder sketched their takeaways onto a larger sheet of paper.

“Inclusivity is a built-in feature, not an add on to the systems we create,” suggested another. It, too, was added to the board.

For the past three years, Lincoln Scholars have concluded their first year of the program with a week-long retreat on leadership and conflict analysis and resolution, hosted by the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution. Wrapped in the lush natural landscape along the shores of Belmont Bay, the scholars embark on a journey of intensive skill-building and planning for how to usher Myanmar toward a democratic future.

The Lincoln Scholarship Program started in 2019 through funding to the Institute of International Education (IIE) by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Burma. Over the course of seven years, 135 emerging Myanmar leaders will be awarded scholarships to study graduate degrees in the United States and receive training in conflict resolution. The intention is for students to return to Myanmar upon graduation to support the growth of their country through socio-economic development, respect for ethnic and religious diversity, and democratic governance.

Two years after the inception of this program, the 2021 military coup overthrew the elected Myanmar government. Now, more than ever, young leaders are Myanmar’s hope for a democratic future.

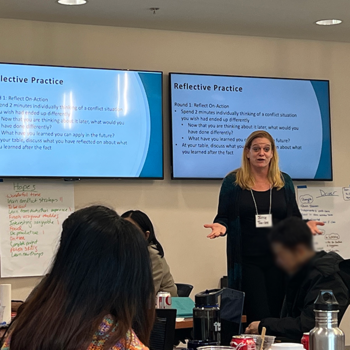

Mason’s Carter School, one of the program’s implementation partners, provides critical learning opportunities for these students as they search for solutions to Myanmar’s tumultuous state. Carter School partners with leadership development instructor Kristine Wood to provide on-arrival orientation to conflict resolution and leadership, re-entry workshops, a two-year online course in Foundations of Conflict Resolution, and the summer seminar at Point of View.

“These students have all demonstrated a passion for leadership and change-making in Myanmar. They need concrete skills and confidence to navigate the complex social conflicts,” said Carter School Associate Dean Juliette Rouge.

Rouge, an associate professor of conflict analysis and resolution, leads Carter School’s efforts with the Lincoln Scholarship Program, including the week-long seminar and ongoing two-year course. “The Mason component provides them with the tools and skills to peace-build in their technical subject areas, such as policy, agriculture, or forestry, as well as using their contextual knowledge of Myanmar to theorize effective, long-lasting change,” she said.

The seminar serves to both expand their understanding of conflict analysis and resolution, and to give these emerging leaders a chance to collaborate on action plans for the betterment of Myanmar. Due to the fraught circumstances of the country, this is, for many of them, their first time getting to work with like-minded individuals with hopes for a return to a democratic Myanmar.

The week is part-training, part-practice. Facilitators guide participants through simulations, roleplay, and working groups, such as the “Perspective Pie,” where students stand in slices with assigned “perspectives” to reflect on a central problem from different angles.

Each cohort creates an action plan to solve Myanmar’s wicked problems. One of the resulting plans from this year’s seminar considered access to education. Since the military assumed control, pro-democracy students no longer have access to higher education in Myanmar, and opposition to military-controlled schools has led to a dramatic decline in attendance in primary schools. The Lincoln Scholars, then, started on a plan for forging alternative pathways to education that would circumvent military control.

Mason is one of the few universities that can do this kind of work because of Carter School’s unique approach to peace building and conflict resolution. “The Carter School method is teaching students how to sit down and understand conflict and resolution from all sides, instead of going in and telling people what to do,” said Jeff Zitomer, director of communications and marketing for Carter School. “We teach our students how to empower people to improve their situation on their own. And there’s not many schools that do that.”

“It's inspiring to watch [the scholars] think through how to make social change in a very repressive society without space for democratic engagement,” said Rouge. “And it’s an opportunity for Carter School to have a direct impact in finding sustainable solutions by working with the people who are impacted by the circumstances, understand the contexts, and are prepared to do the work.”