In This Story

Nearly two dozen George Mason University faculty members, from seven Mason schools and colleges, provided their expertise to the 120 Initiative, an all-hands-on-deck effort from the 18 institutions in the Consortium of Universities of the Washington Metropolitan Area to find solutions to reduce gun violence.

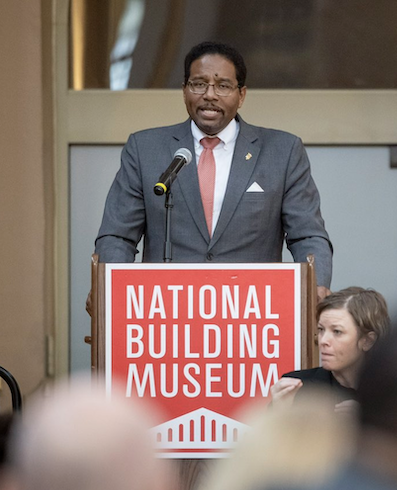

Named for the average number of people who die each day from gun violence, the 120 Initiative announced its findings this week ahead of an event Wednesday at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. Faculty members from across the consortium emphasized that their work must lead to action and many that community-level solutions can work as well as broader solutions.

Through a series of virtual and in-person sessions over the past several months, more than 100 faculty experts from across the region identified actions that could make an immediate impact on gun violence, while acknowledging that gun violence merits further study and emphasizing that most measures could be more effective when paired with legislation.

The top three recommendations are:

- Expand and build upon effective community engagement and violence interruption programs.

- Explore anti-gun violence prevention messaging and education campaigns, while respecting law-abiding gun owners.

- Expand use of safety devices and safety training.

The faculty explored several other recommendations, also outlined in the group’s white paper.

In June 2022, Mason President Gregory Washington and University of Maryland President Darryll Pines charged consortium faculty members with identifying practical, actionable, and nonlegislative solutions to reducing gun violence.

“These recommendations are directly inspired by the tragedy in Uvalde, Texas, which caused the nation to cry out for someone to do something to finally end the nation’s epidemic of gun violence,” Washington said. “Our faculties have come together to offer solutions that can be implemented alongside wise legislation, adapted to broad varieties of communities, and address this problem at its roots. We don’t have to feel helpless to the problem anymore.”

Faculty produced diverse yet intertwined ideas through open communication, lively and at times contentious debate, and a shared sense of purpose.

“There was definitely this perspective of we need to do something, and we need to do something now,” said Mason global and community health professor Carolyn Drews-Botsch. “To some extent, it wasn’t the usual pontification. There was definitely more of a feeling of urgency and we can’t come up with the Cadillac version of things, we have to come to actionable ideas now.”

Mason faculty were major players across the various working groups, forming new alliances within the university and around the consortium, with disciplinary lines diverging throughout the process.

Carter School conflict resolution professor Patricia Maulden focuses on social militarization and violence becoming part of the social fabric in communities and accepted as normal. Her work in the initiative involved finding ways through engagement, awareness, and education to empower and activate community voices to help reduce gun-related violence instead of accepting violent outcomes with a collective helpless shrug.

“The violence takes place in communities. People are shot to death in communities. Schools, malls, parks are in communities, and it is in these spaces that blood is spilled and people die,” said Maulden, director of Mason’s Dialogue & Difference Project. “To live in a community is to be part of the social fabric, and massive gun violence as we are seeing now is part of that fabric, woven tight through constant exposure without response, the normalization of the unthinkable, the depravity of disregard.”

One of her Carter School colleagues, peace and conflict professor Arthur Romano, said community members develop unique insights into gun violence, racial oppression, and other forms of systemic harm. Nonviolence education can help communities to disrupt and transform cycles of violence.

“What lies on the other side of a society impacted by violence and profound inequality?” Romano said. “The most robust and creative answer to that question, the visions for alternative futures, have most often come not from universities alone but from community members that know all too well how we are falling short and where we need to grow as a society.”

Stephanie Dailey, a professor in the Counseling and Development Program in the College of Education and Human Development, worked with colleagues from Mason and five other universities in a group that focused on engaging communities and educating and building skills, particularly in underrepresented communities.

Dailey, former chair of the American Counseling Association Foundation, noted that counselors are uniquely positioned to identify and address mental health concerns that may contribute to the risk of gun violence, including exposure to violence, engaging in high-risk behavior and a lack of equitable access to education and health resources. Stigma around seeking help and deficiencies in mental health support services within the community are other factors.

“Counselors understand generational, complex trauma and can use this information to help promote policies and programs that support prevention, intervention, and programs to reduce gun violence,” Dailey said.

University Professor Faye Taxman, director of Mason’s Center for Advancing Correctional Excellence, based in the Schar School of Policy and Government, focused on the criminal legal system not being the first stop in trying to address individuals prone to gun violence, either as victims or perpetrators.

“We can’t depend on the criminal legal system as we have in the mass incarceration era because individuals do not feel that they are treated with respect,” Taxman said. “We have to look for addressing other social issues related to employment, social supports, and helping individuals see themselves as vital members of our communities. Prosecutors and police can reinforce the importance of noncriminal legal system efforts.”

Scalia Law School professor Robert Leider was part of a group that examined law enforcement solutions to gun violence. This led to vigorous debate, including about how to frame the problem. Many consider gun violence to be a national issue. Leider sees it as more of a local issue because of recurring violence in specific locations.

“Somebody said at one point you can’t prosecute your way out of it, and that’s true, but you can’t ignore the prosecution side because that’s part of a viable strategy,” Leider said. He thought his group perhaps could have produced stronger enforcement recommendations, but it was difficult to come to a consensus on a divisive aspect of a divisive issue.

“It’s terrific to have those resources and to have those voices in the conversation, and it also gives you a very good interdisciplinary perspective,” Leider said. “Solutions to gun violence will pull from a number of disciplines. It’s an important conversation to have.”

Drews-Botsch, the global and community health professor, was in a working group that examined structural determinants of gun violence. Suicides account for about half of all gun-related deaths, so possible solutions include greater use of gun safes or gun locks, waiting periods that help stave off impulsive actions, the prevention of marketing of guns in vulnerable communities, and education and training regarding gun safety.

“If you don’t have access to a gun in a suicide attempt, then it tends to be a less lethal suicide attempt, and if it’s the result from impulsive behavior, it provides some means for intervention,” Drews-Botsch said, adding that universities can show leadership by banning guns on their campuses and by forming relationships with at-risk communities.

School of Business professor Ashley Yuckenberg was in a group that looked at ways the media covers mass shootings and how extensive reporting about the perpetrator could influence others to try to gain similar notoriety. She said there is a difference between how the media covered the Columbine shootings in 1999 and the Parkland shootings in 2018. Focusing coverage on the victims and how the shooting affected the community is less likely to inspire copycats.

“We’re very interested in educating the public about the information that they consume on mass shootings and being aware that by providing some publicity to the shooters there can be some perpetuation of these crimes,” Yuckenberg said. “Reaching out to younger community members who are the typical person who might commit these crimes and giving them other options and some of those interventions earlier on seem to make a big difference.”