George Mason University historian Yevette Richards Jordan focuses her research lens on African American history, with an emphasis on racist violence from the 1920s through the 1940s. For the past several years, however, her work has led her to uncover a hidden history of racial violence that struck her own family, and the trauma of that violence that continues today.

“I’ve been researching racist violence in northern Louisiana for probably about a good six years,” said Richards, an associate professor in the Department of History and Art History of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences. “I became interested in it through stories that I’d heard from my family about lynchings that had occurred—and one particular lynching I could find no evidence of for years and years. It was a very violent incident in which a 13-year-old girl named Carrie Lee, but called Blossom, and a 22-year-old mother, named Mary, were killed, and their own mother Lizzie was shot, and their sister-in-law Emma was shot.

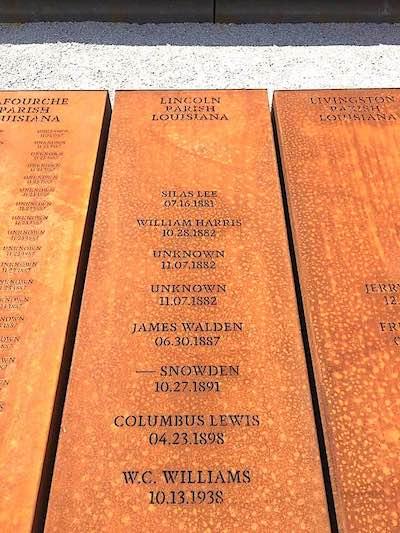

“Years later I found references to this violent event and the victims were listed as ‘unknown,’ ‘unidentified.’ I knew the backstory and I could connect this backstory to these names and these unnamed persons.”

With the help of a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Richards will continue to pursue the details of this hidden narrative. Her project, Between Piney Woods and Cotton Fields: Tracing Racist Violence through Family Networks of Northern Louisiana, received $60,000 in funding, part of the NEH’s August 2022 announcement of grants that will support humanities projects nationwide. In his announcement, National Humanities Alliance executive director Stephen Kidd stressed the importance of the projects being funded. “We are immensely proud of the NEH’s impact across the U.S. and will continue advocating for increased federal support for future grants in 2023 and beyond,” he said.

Richards’s work illustrates this impact. Her project examines multigenerational family networks in early 20th-century Louisiana, and their connection to broader racial dynamics and power structures in the United States. The research cuts close to home.

“There are two lynching events: the Taylor sisters, and then W.C. Williams,” said Richards. “And I’m not directly related to W. C. Williams, but I have cousins who are related to him. So I am also able to see how Black families are interconnected. Black families who are the victims are interconnected.”

The Williams incident was well known, she said. “His lynching in 1938 represented the last mass daytime lynching in Louisiana, and thousands of people came out to view his body.”

She had a more difficult time learning about the Taylor sisters. “I found that I’m related to them through my mother’s side—her grandmother,” she said. “I first learned about the Taylor sisters through my cousins, the Caldwell cousins, who told me that their father’s first wife had been lynched. No one ever mentioned it, and it was just a vague memory for many of my other older cousins. But these particular Caldwell cousins told me that their father would talk about his first wife, Mary, usually around Christmas, and talk about what happened. But there were few details about the Taylor sisters that they knew beyond this immediate violent event.”

Richards’s search for information has been hampered by the age of many of the people who knew the truth about the Taylors and Williams, but also by their concern for safety. “Some people never spoke to me,” she said. “They’re elderly, in their 80s and 90s, and they would say a little bit but then they would avoid me. I tried to be sensitive to the fact that they’re still living there, and even though they’ve outlived many of the people who were perpetrators, they realize that their descendants still live there, and the fear was so great at the time that this violence happened, it still carries over with them.”

Richards has also found a relatedness among the perpetrators of the violence. “As I researched the incidents, I came to see that many of the white family members were interconnected; they were connected to each other as cousins,” she said. “Looking at the white family networks, I also began to see the connections that they had with state power. And with the police and judges. And many of them were Klan leaders, as well, leaders of the 1920s Klan. This evidence helped me to understand how this violence could remain so submerged and hidden.”

Despite the obstacles in tracing the lives of the Taylor sisters, W. C. Williams, and the people who have sought to erase those memories, Richards perseveres in bringing the stories to light. "I’ve already developed, with my graduate students, a course on race and lynching,” she said. “That course has helped me in my background research into this area. Once this book is written, it will be included in that course.”