Beth Lattanzi, an instructor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, teaches students how to test materials’ strength, ductility, hardness, and fatigue life using state-of-the-art equipment in ME 311: Mechanical Experimentation, a one-credit lab course. Students must social distance during the class. Photo by Evan Cantwell

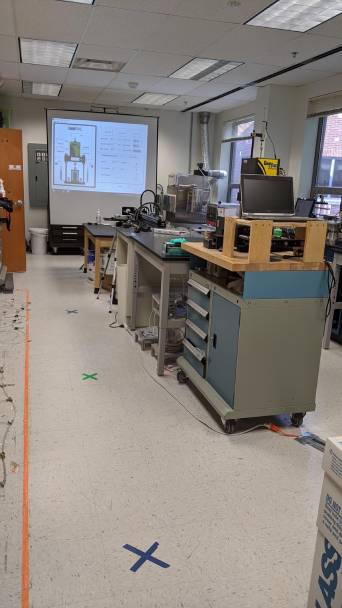

Laboratory workstations are spaced far apart and cleaned between students for the civil engineering master's course, CEIE 636: Sources of Geotechnical Data. Students get hands-on experience in quantifying and assessing the properties of soils in the course taught by Burak Tanyu, associate professor in the Sid and Reva Dewberry Department of Civil, Environmental, and Infrastructure Engineering.

Students in a civil engineering graduate laboratory course, CEIE 636: Sources of Geotechnical Data, are physically distanced during a lecture portion of the class.

Engineers are by nature problem solvers, so the challenge of what to do about teaching labs during the pandemic gave Mason Engineering faculty a chance to use their ingenuity to develop flexible courses for fall 2020.

They spent hours over the summer designing a variety of instructional plans from in-person laboratories that meet the Safe Return to Campus guidelines to hybrid labs that include both virtual and face-to-face components to online labs in which students can do their work remotely if all classes suddenly become virtual because of an outbreak of COVID-19 on campus.

The Department of Bioengineering had to recalibrate BENG 371: Bioinstrumentation and Devices Laboratory, a one-credit course that introduces students to the concepts and electronic tools needed to make biomedical measurements, says Randy Warren, an adjunct faculty member who teaches the class and is the department’s lab manager.

Two sessions of the lab with a total of 26 students are offered in two large lab rooms in Peterson Hall on the Fairfax Campus.

“Students build circuits, test them, and see the responses,” Warren says. “Most have had no experience in this area outside of what they learned in physics. It’s their first time working with this type of equipment. It’s kind of like jumping off the deep end of the pool.”

Last fall, undergraduates worked in pairs in the labs, but because of social distancing guidelines, students are now at individual workstations, which the department increased from nine to 16. These stations’ equipment includes an oscilloscope, a digital multimeter, and an analog/digital trainer; all must be cleaned between classes.

A few students chose to do the class virtually, so the department assembled $400 portable lab kits that students can use at home while watching the lab class online. “They have some of the same equipment as the lab, but it’s not as elaborate,” Warren says.

In case the university must pivot to total distance-learning classes, the bioengineering department is making enough portable test kits for everyone in the class, he says.

The department had to “jump through some hoops,” Warren says. But it’s worth it because “we are trying to provide the same or better level of education in a more challenging environment.”

Similarly, Beth Lattanzi, an instructor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, worked approximately 150 hours over the summer to develop contingency plans for the 81 students taking ME 311: Mechanical Experimentation, a one-credit lab course in which students take experimental measurements in solid mechanics and materials science.

In the lab on the Science and Technology Campus, students test materials’ strength, ductility, hardness, and fatigue life using state-of-the-art equipment, such as automated hardness testing machines made by the manufacturer Tinius Olsen. “I love this particular class because it’s the first time they get to do a whole semester of hands-on work, and I wanted to maintain that,” Lattanzi says.

Usually, students have one lab a week for the semester, but this fall, they’re coming in once every three weeks to meet physical distancing guidelines, she says.

The other two weeks, students conduct experiments at home that illustrate other concepts they’re learning in the co-requisite course, Material Science. “I’ve made videos showing the procedure as we do it the lab, and the at-home version is analogous but without the big equipment,” she says.

Lattanzi packed 81 experimentation kits with the necessary supplies to run the experiments at home. If the university switches to total distance learning, “I’m going to get even more creative,” she says.

Burak Tanyu, associate professor in the Sid and Reva Dewberry Department of Civil, Environmental, and Infrastructure Engineering, developed a different strategy for the lab he’s teaching this semester.

In his three-credit course, CEIE 636: Sources of Geotechnical Data, students get direct experience in quantifying and assessing the properties of soils. These properties are key factors in designing engineered infrastructures such as foundations, embankments, and earth-retaining structures, as well as assessing the stability of slopes, he says.

“Soils are produced from the weathering of rocks based on the geological processes that take place over a long time,” Tanyu says. “No soil type is the same, even though we may just call them clays or sands. Therefore, students need to have hands-on experience in our laboratory that would not be possible to achieve through virtual learning.”

Tanyu has 12 students in this class. He is teaching this semester with a co-instructor, Aiyoub Abbaspour, to ensure a high-quality education while also implementing all the safety rules for COVID-19.

For example, students are divided into three groups. While one group learns the background and theory associated with an experiment, another group watches how to set up the experiments demonstrated by the instructor via a projector then works in the laboratory by rotating one by one to conduct the tests.

While in the laboratory, each student stands at designated spaces that are marked on the floors with an X. The three workstations are sanitized with alcohol between students’ rotations.

Tanyu hopes that the effort they are putting into the face-to-face lab pays off “with students thoroughly learning the material.”