“I’ve never been so stressed in my life,” says one research participant—a teacher and mother of three—as she tries to balance teaching online, helping her children with online schooling, and while her husband is also teleworking—all because of the “new normal” created by the COVID-19 pandemic. The influence of these stressors on families is just one of the factors that researchers in the College of Health and Human Services at George Mason University will track as part of the Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Program.

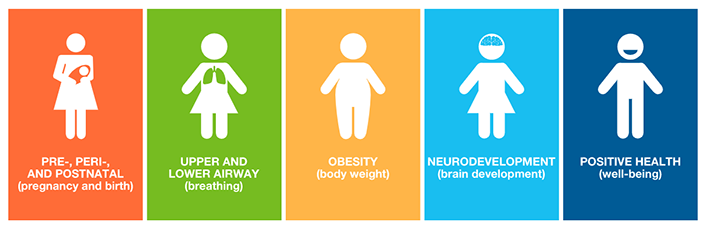

The College is a collaborator in the ECHO Program, a seven-year initiative funded by the National Institutes of Health, whose aim is to understand the effects of environmental exposures on children’s health and development. ECHO teams across the country investigate the impact of different types of environmental exposures on five key pediatric outcomes: adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes; airway function; obesity; neurodevelopment, and health and well-being. The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai leads the research with Mason serving as one of three collaborating sites focusing exclusively on the pediatric population.

ECHO teams across the country investigate the impact of different types of environmental exposures on five key pediatric outcomes.

Mason ECHO has already recruited more than 350 participating families and is part of a new set of research initiatives in the College made possible with the opening of the Population Health Center on the Fairfax campus. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the research team conducted in-person assessments with study participants who were seen in the Center. However, like every other aspect of everyday life, the ECHO study pivoted to remote data collection on March 19, 2020 with resounding success. Still, we look forward to reconnecting in-person with our families in the near future.

“The mission of ECHO is to enhance the health of the generations to come,” explains Dr. Kathi Huddleston, principal investigator of Mason ECHO. “When our physical doors closed due to COVID-19, it opened a window that will give us insights into COVID-19.”

ECHO is the first national longitudinal childhood study being conducted during a pandemic. With longitudinal data collection, the research team will be able to assess how environmental stressors and the pandemic impact children and mothers’ health.

Since beginning recruitment in January 2020, the Mason ECHO study has recruited 350 participating families, while pivoting to use remote data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As part of ECHO’s study protocol, nasal swabs are being collected in the home by mothers for both children and themselves. These biospecimens will provide additional insights into the spread of COVID-19, since they were collected before, during, and after the pandemic and may provide valuable information about children’s prevalence of disease. The team has begun to develop ways to stay engaged with participating families by collecting other biospecimens (hair, toenail clippings, and deciduous teeth) for the measurement of environmental chemicals. Since hair usually grows a half an inch a month, this allows researchers to “see” patterns —creating a timeline of stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Families with scales can also report weight measurements to help understand the impact of sheltering in place on children’s growth and development.

“I am tremendously grateful to the Mason ECHO research team and study participants who are working together to generate data that scientists will analyze to better understand the full impact of the environment on children’s health and well-being,” says Dr. Germaine Louis, dean of the College. “Children live and thrive in the environment and keeping them safe and healthy is our overarching goal.”

“By changing our procedures to focus on COVID-19 related concerns, we have an unprecedented opportunity to understand how living through a pandemic affects the health of NOVA families,” explains Huddleston.

Some COVID-19 health questions that families are being asked in the new Mason ECHO surveys include: whether anyone has been diagnosed with COVID-19, whether sheltering in place orders are being followed, sources of news and information, and how the pandemic is affecting other aspects life, such as employment status, social services, and stressors. Mothers are reporting higher levels of stress during the pandemic.

“We’re already seeing evidence of vast health disparities across our country with the COVID-19 pandemic,” explains Huddleston. “We know the COVID-19 response such as sheltering in place can look very different for people depending on their family composition, socio-economic circumstances, and a host of other factors. There could not be a better time to focus on capturing those impacts of the pandemic as we continue to study the environmental influences of child health.”