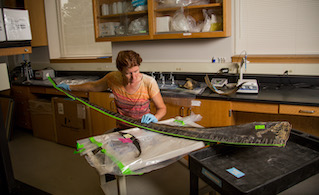

Mason biology professor Kathleen Hunt is part of a team of researchers working to understand how whale foraging and reproduction changes over time. Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University

Commercial whaling removed nearly two million whales from the Southern Ocean, but little data exists from periods before the predators were removed, limiting researchers' understanding of past ecosystem function, predator adaptations to the Antarctic, or direct tests of relevant theories.

However, an archive of baleen plates from 800 Antarctic blue and fin whales harvested between 1946 and 1948 was recently rediscovered in the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History.

George Mason University biology professor Kathleen Hunt is part of a team of researchers, supported by a National Science Foundation grant, working to understand how blue and fin whale foraging and reproduction respond to climate variability, changes in the food web, and whaling. The team includes Alyson Fleming of the University of North Carolina Wilmington, and Ari Friedlaender and Matt McCarthy of the University of California Santa Cruz.

Wildlife endocrinologist Kathleen Hunt has pioneered novel ways to analyze hormone levels in whale baleen. Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University

Why should average citizens care about this work?

Via email, Fleming said, "Blue and fin whales (Balaenoptera musculus and B. physalus) are the two largest krill predators in the Southern Ocean and the two largest animals on the planet. Despite decades of whaling, little data exists on basic aspects of their foraging behavior and population dynamics either during or after commercial whaling."

This has prevented rigorous investigation of their role in the historic Southern Ocean ecosystem, which was likely significant.

"The lack of historic and modern data has thus resulted in a major gap in understanding these species’ adaptations to the Antarctic environment as well as broader ecosystem function," she said.

Hunt is a wildlife endocrinologist with a strong interest in applied conservation physiology. An expert in hormone assay validation, she has developed hundreds of hormone assays for alternative sample types that can either be collected noninvasively without disturbing the animal (feces, respiratory vapor) or can be found in museum archives (baleen, fur, feather).