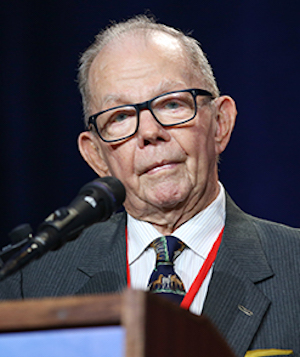

Lee Talbot. Photo courtesy of International Institution for Sustainable Development.

The Trump administration’s recent decision to roll back regulations on the Endangered Species Act substantially increases the probability that species will become extinct and ecosystems will suffer, said George Mason University environmental science professor Lee Talbot.

The administration says the changes will ease regulations on businesses and industries like mining and oil drilling. But Talbot said the changes weaken rules meant to protect threatened and endangered animals, reducing the amount of habitat reserved for wildlife and removing tools that could predict future harm to them.

“All of this is to make it easier for petroleum and other industries to expand and shield their activities,” said Talbot, one of the original authors of the Endangered Species Act, who was the chief scientist and foreign affairs director of the President’s Council on Environmental Quality under presidents Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter.

The result, he said, is an assault on America’s natural heritage, allowing economic factors to be considered in whether or not a species is saved.

“The ESA intentionally kept economic factors out of the decision making on species listings,” Talbot said. “We recognized that perceived short-term economic factors could overcome the scientific urgency associated with threatened and endangered species.”

Signed into law in 1973, the Endangered Species Act protects more than 1,600 species in the United States and its territories and has saved 99% of listed species from extinction.

“When a species becomes extinct or a habitat is lost to development, the effects are irreversible; a piece of our natural heritage is lost to both present and all future Americans,” Talbot said.

Several polls have shown a majority of Americans are in favor of supporting endangered species, but the changes to the Endangered Species Act reveal the Trump administration prioritizes profit over protection, Talbot said.

“The administration generally has put industry insiders who oppose government regulation into key positions in the agencies that manage America’s natural heritage and health,” he said. “The interest of these officials is to support their industries.”

Though the rollbacks pass control of America’s natural heritage from conservationists to those favoring short-term economic benefits, action can be taken, Talbot said.

The public could express its concern through contacting the White House, relevant senators and congressmen. Congress could act to reverse the decision, and court actions to stop the decision could be brought by concerned NGOs and individuals, Talbot said.

“Until the 1980s the United States was, and was regarded as, the leader in conservation of a nation’s natural heritage, a position that we have abdicated in the present administration,” Talbot said. “It remains to be seen what global effect the Trump administration’s anti-conservation position will have.”

Lee Talbot can be reached at 703-993-4037 or ltalbot@gmu.edu.

For more information, contact Mariam Aburdeineh at 703-993-9518 maburdei@gmu.edu.

About George Mason

George Mason University is Virginia’s largest public research university. Located near Washington, D.C., Mason enrolls 38,000 students from 130 countries and all 50 states. Mason has grown rapidly over the past half-century and is recognized for its innovation and entrepreneurship, remarkable diversity and commitment to accessibility.