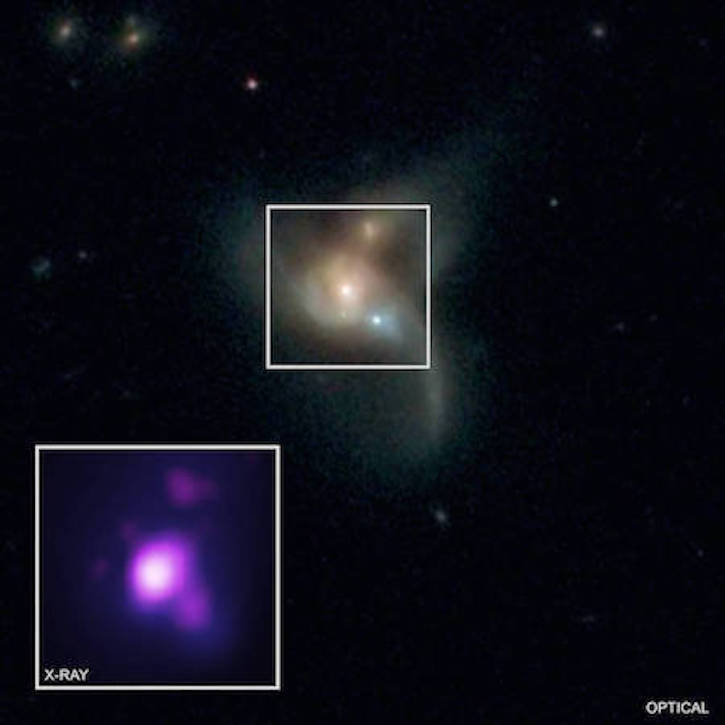

Mason researchers discovered the pending collision of three galaxies. Photo courtesy of NASA.

A team of George Mason University researchers has discovered a rare trio of three supermassive black holes in a system of three merging galaxies a billion light-years away.

Mason PhD student Ryan Pfeifle and his thesis advisor, professor Shobita Satyapal, co-authored a study that reveals the location of three gigantic black holes set on a collision course—each galaxy has a black hole at its center. Confirmed cases of three galaxies colliding are extremely rare. The team’s study, which can be found in the latest edition of Astrophysical Journal, has drawn worldwide interest because it offers new ways to discover these mergers. The research was cited in the New York Times and on CNN.

“What we have here in this paper is really one of the most compelling cases for one of these types of systems,” said Pfeifle, a second-year PhD student who completed his BS in physics at Mason in 2017. “We think mergers are incredibly important sites where black holes can grow. It’s likely the black holes grow the most during these events because there’s so much gas and dust driven into the centers of the galaxies during these events.”

The researchers were originally looking for pairs of black holes in merging galaxies when they discovered that one of the systems had evidence of three monstrous feeding black holes.”

The advanced stages of black hole mergers are predicted to be the sites where lots of gas and dust are driven to the galaxy centers, where they can feed the central black holes, Pfeifle said.

Using high-powered ground and space telescopes to take a closer peek at the frenetic activity taking place roughly one billion light-years from Earth, the team of scientists soon realized they had stumbled upon a rare finding with three galaxies nearing a collision.

“Dual and triple feeding black holes are very rare,” said Satyapal, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy within Mason’s College of Science and leader of the black hole galaxy research group at Mason. “But such systems are actually a consequence of galaxy mergers, which we think is how galaxies grow and evolve.”

Ryan Pfeifle

Gas and dust emanating from supermassive black holes typically make it difficult to see light coming from supermassive black holes, but the researchers got around that hurdle by using infrared and X-ray images.

NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory detected strong sources of X-ray light near each of the merging galaxy centers, indicating that lots of gas and dust were being consumed there by a feeding black hole. Observations from the Large Binocular Telescope, or LBT, in Arizona led by Barry Rothberg, were critical in confirming these active black holes.

NASA's Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array spacecraft, or NuSTAR, also spotted evidence of gas and dust circling one of the supermassive black holes.

“Through the use of these major observatories, we have identified a new way of identifying triple supermassive black holes,” Pfeifle said. “Each telescope gives us a different clue about what's going on in these systems. We hope to extend our work to find more triples using the same technique.”

These galaxy mergers can potentially lead to the black holes eventually merging, giving rise to the loudest gravitational wave signals in the universe, Satyapal said, offering additional clues about the history of the universe, gravity and properties of black holes.