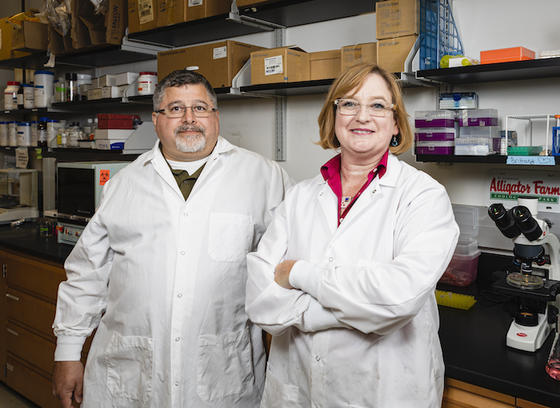

George Mason University researchers Monique van Hoek and Barney Bishop and their collaborators have released their findings on sequencing the Komodo dragon genome, revealing multiple clusters of antimicrobial peptide genes that could prove instrumental in the fight against multi-drug resistant bacteria.

Their work, which was published in the latest issue of BMC Genomics, identified key clusters of Komodo dragon antimicrobial peptide genes, which are protein-like molecules that contribute to the front line defense of its immune system.

Komodo dragons are resilient reptiles with robust immune systems that regularly dine on dead and decaying flesh and whose saliva is known to be rich in bacteria.

“They appear to be unaffected, suggesting that dragons have robust defenses against infection,” the two scientists wrote in the paper.

Major classes of the antibacterial peptides found in Komodos and other vertebrates include cathelicidins and beta-defensins. Their analyses revealed novel Komodo dragon defensin genes that appear to be unique to these animals. These cathelicidin and defensin antimicrobial peptides may contribute to the Komodo dragon’s robust immunity and apparent resistance to infection and could provide critical clues to aid in the human fight against multi-drug resistant bacteria, which is an emerging medical crisis in health care, and spur faster wound healing.

“The hope is that this could lead to something that could be developed into medicine to combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria,” said van Hoek, a professor in the School of Systems Biology in Mason’s College of Science.

She and Bishop, an associate professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry in the College of Science, reported the sequencing, assembly and analysis of the Komodo dragon genome, with a focus on innate immunity genes and biomolecules that contribute in defending against infection, particularly antimicrobial peptide genes.

The two scientists had previously identified unique antimicrobial peptides in the plasma of Komodo dragons and alligators, and have now added to their earlier research by identifying antimicrobial peptide genes in the Komodo’s genome.

Van Hoek and Bishop have been collaborating since 2009 to study antimicrobial peptides and their activity against important bacterial pathogens. More information about their collaborative work can be found at adr.gmu.edu.

Mason has a long history with Komodo dragons. In 1992, on the Fairfax Campus, Mason biology professor Geoffrey Birchard watched over the first Komodo dragon eggs to be hatched in captivity in the United States.

Growing to lengths of up to 10 feet, Komodo dragons are the largest living lizards on the planet and are believed to have evolved in Australia. They are the sole survivor of the mega fauna that once populated Australia and south Pacific Islands, including those of Indonesia. Komodo dragons are endangered and actively conserved, with Komodo National Park in Indonesia being a UNESCO World Heritage site.