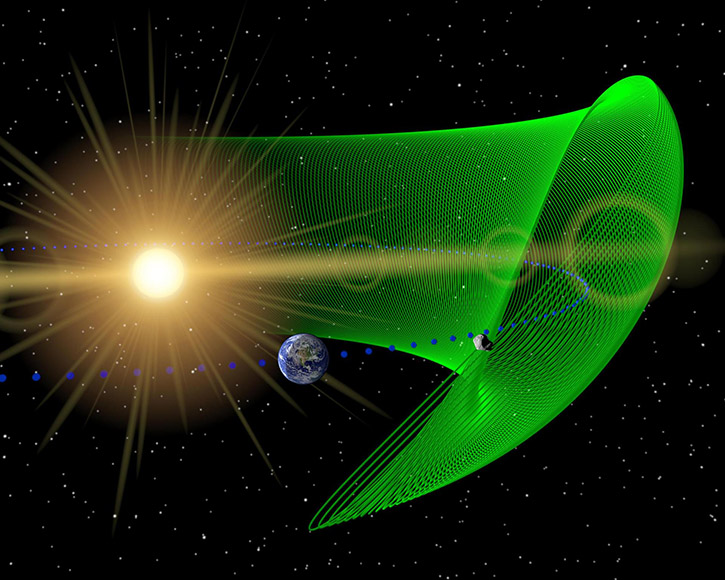

This artist concept illustrates the first known Earth Trojan asteroid, discovered by NEOWISE, the asteroid-hunting portion of NASA WISE mission. The asteroid is shown in gray and its extreme orbit is shown in green. Objects are not drawn to scale. PHoto illustration courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA.

A George Mason University researcher stands ready to help coordinate the world’s response should a planet-killing asteroid ever threaten Earth.

“The possibility is still very low,” said Chaowei Phil Yang, the director of Mason’s Center of Intelligent Spatial Computing, “but we still need to be prepared.”

Yang and his team are constantly scanning the heavens for threats large enough to do significant harm. It’s Yang’s job as part of the NASA Planetary Defense Coordination Office to collect data and to guide efforts within the U.S. Department of Defense, NASA and space agencies from around the globe while also devising simulations to stave off potential disaster if things ever become that dire. Yang works in support of NASA’s Myra Bambacus of the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.

“Basically, we’re addressing the potential threats from outer space,” he said.

Scenarios include using space-delivered nuclear weapons that could potentially obliterate an oncoming asteroid or at least nudge it enough from its path to avoid hitting Earth.

Using the Hubble Space Telescope and other observation capabilities, the consortium of NASA scientists from various labs across the country study huge asteroids that are still many light years away to simulate potential travel paths, as well as any potential impact on Earth, Yang said.

In much the same manner as blockbuster movies like “Armageddon” or “Deep Impact.”

Established by Congress in 2016, the Planetary Defense Coordination Office is charged with detecting, characterizing and mitigating any potential threats to Earth from outer space. The aim is to provide the key decision-makers, scientists and organizations all the real-time information needed to deal with potentially hazardous asteroids.

Congress acted in the wake of the viral video of the 2013 occurrence in Russia, where a 20-meter asteroid smashed into the ground at 40,000 mph. The asteroid missed hitting any large population areas and resulted in just minor injuries.

Earth might not always be as fortunate, as the planet is constantly pelted by asteroids, Yang said. Most are small enough that they burn up in the atmosphere, but an extremely big one could prove catastrophic.

A huge asteroid that created a gaping 60-mile-wide hole is believed to have killed off the dinosaurs roughly 66 million years ago. Earth’s climate changed as a result of the remaining smoke and debris in the air that blocked the sun, killing vegetation and disrupting the planetary food chain.

Yang stressed that another such likelihood was extremely remote, adding that scientists now have the means to locate asteroids some 10 to 20 years before they would come within striking distance of the planet.

“If they’re big enough,” he said, “we can find them soon enough.”

Helping Yang is a team of students that includes Joseph George, Alena M. Deveau, Rob Culbertson, Yongyao Jiang, Han Qin, Yun Li, Manzhu Yu, Mengchao Xu and Han Qin.