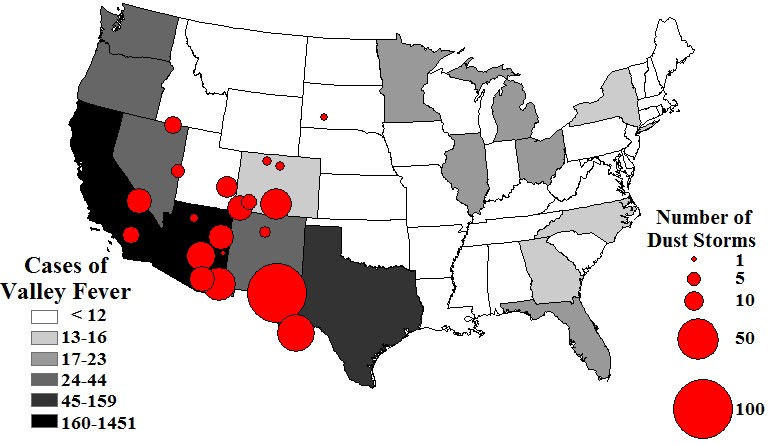

Dust storms spike with Valley fever cases. The nation’s largest number of dust storms from 1988 to 2011 are concentrated in the Southwest states – the same states reporting the nation's highest numbers of Valley fever cases. Map courtesy of NOAA.

A dramatic spike in recent years of cases of a potentially fatal respiratory disease and the growing frequency of severe dust storms throughout the American Southwest could be directly linked, according to a new national study led by a George Mason University researcher.

The journal Geophysical Research Letter recently published the findings of Daniel Q. Tong, a professor with George Mason’s Center for Spatial Information Science and Systems, and his team from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NASA, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and other universities. Their research suggests there may be “more than a casual relationship” between the two phenomena, he said.

“The similarity in the spatial distribution of dust storms and Valley Fever incidences points to a potential connection between the two,” the researchers wrote.

Severe dust storms devastated the Southwest and many parts of the Midwest in the 1930s when an extended drought―coupled with high winds, economic depression and poor land management―created the environmental catastrophe known as the “Dust Bowl.”

It was while initially researching the likelihood of another Dust Bowl that Tong and his team first became aware of the spike in Valley Fever cases.

Easily spread by wind, Valley Fever is a fungal infection caused by soil-dwelling coccidioides (kok-sid-e-OY-deze) organisms and causes flu-like symptoms, including extreme fatigue, chills and night sweats. If the disease is left untreated, the spores can disseminate throughout the blood stream and eventually cause lifetime health problems or even death. Valley Fever accounted for more than 3,000 deaths between 1990 and 2008, according to a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Overall, there was an 800 percent increase in Valley Fever infections throughout the Southwest from 2000 to 2011, according to Tong’s NASA-funded research findings. Kern County, Calif., has been among the hardest-hit areas, as more than 1,900 residents were infected and six died in 2016.

Tong’s research showed there has also been a 240 percent uptick in the number of large dust storms over the past two decades. The majority of new Valley Fever infections were reported in the areas where increased dust activity had been detected.

Climate models have indicated a continued drying trend in the southwestern United States that is expected to lead to more dust storms thanks to the region’s arid conditions and the tiny changes of sea surface temperature in the northern Pacific Ocean, Tong said. The change of sea surface temperature brings more northerly winds that are colder and drier than those from the south. That means less water vapor to the Southwest and drier conditions ripe for dust storms.

“As cocci fungi can be transported into cities by these storms, it is possible to see more Valley Fever outbreaks,” said Tong, who is also a member of NASA’s Health and Air Quality Science Team.

Dust storms have also been linked with other respiratory diseases such as asthma and bronchitis.

Further information about Tong’s research on the possible link between Valley Fever and dust storms can be found at www.noaa.gov/media-release/spike-in-southwest-dust-storms-driven-by-ocean-changes.