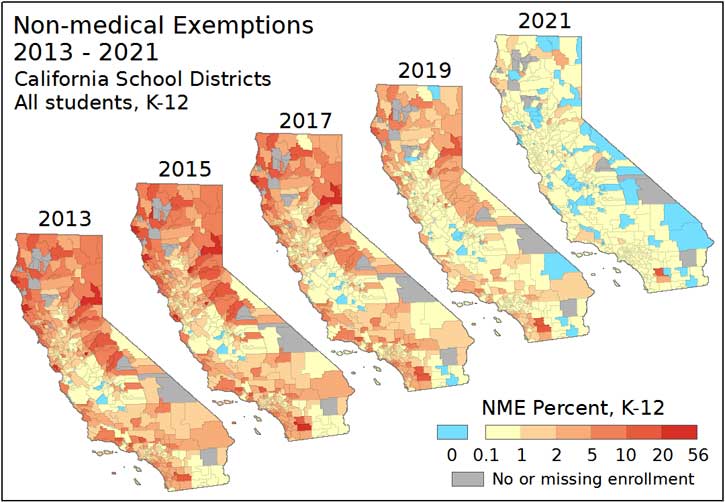

These maps show non-medical vaccination exemption rates for school districts in California before and after the passage of S.B. 277. Red portions of the maps indicate areas where up to 56 percent of students have non-medical exemptions. Green portions of the maps indicate areas where 0 percent of students have non-medical exemptions. Courtesy of the researchers.

George Mason University researchers are using new methods to study the outcome of recent California vaccination legislation and highlight potential outbreak hot spots.

What they learn from California could be a test case for the rest of the country.

George Mason researchers Paul L. Delamater, Timothy F. Leslie and Y. Tony Yang are using a novel approach that combines geographic information system (GPS) mapping and data to illustrate regional pockets with lots of nonvaccinated children.

Mason researchers will be tracking how California legislation changes the vaccination rate throughout the state. Their work also can highlight regions primed for disease outbreaks. Some other notable areas of nonvaccinated students include Northern California near Eureka, Santa Cruz and north of Lake Tahoe.

The new geographic methods Delamater is developing are helping infectious disease epidemiologists understand how people come in contact with one another, said epidemiologist

Kathryn H. Jacobsen, a professor of the Department of Global and Community Health in Mason's College of Health and Human Services.

“Outbreaks happen when people cross paths with one another in their home neighborhoods, at school or work, or at other locations,” Jacobsen said. “Dr. Delamater is creating new models for mapping the probability of a contagious person having contact with susceptible people in various settings. Places where a large number of children remain vulnerable to infectious diseases because they have not been vaccinated have a higher risk of outbreaks.”

Nonmedical vaccination exemptions have allowed parents to opt-out of requirements to vaccinate their children for religious or personal belief-related reasons. California legislators eliminated nonmedical exemptions in 2015 with California Senate Bill 277, but the bill had a “grandfather clause” to allow students who already had nonmedical exemptions to keep them. Those students will be in the school system until 2021.

There were about 164,000 California students with nonmedical exemptions in 2015. That number is expected to drop to about 94,000 in 2018 and to zero in 2022. Mason researchers show in a recent paper why the law will take time to achieve its goals.

Individual decisions impact collective public health, said Delamater, who along with co-author Leslie, is a professor in Mason’s Department of Geography and Geoinformation Science.

"But when we start looking at a population and we see that multiple people have made a decision, all in the same geographic region, now we start seeing risk for everyone involved, the whole population, not just those individuals," Delamater said.

For their study, the researchers obtained vaccination exemption and school enrollment data for students entering kindergarten, seventh grade and seventh- through 12th-grade in public and private schools in California.

The researchers then constructed models of K-12 students in California schools between 2011 and 2022.

They found that while California will eventually attain a nonmedical exemption rate of zero, the pace at which various communities within the state will arrive at that point will vary because of the build-ups of students with nonmedical vaccination exemptions in some regions. Many regions started with high numbers of exemptions, while some started with low numbers.

Yang said this study offers a takeaway for legislators across the country.

"The lesson learned for other states is that they need to look at empirical data when they are proposing a similar grandfather clause. They need to examine the consequences of this approach, which overlooks undesirable effects that numerous regions of the state could continue to be at risk of vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks," Yang said.